Today I realized the internet actually comes from somewhere. That might sound silly, so think of it in Santa Claus terms. Until I was 9, I never put much thought into the concept of Santa Claus. He appeared when he was supposed to and did was he was supposed to. Then one day, I applied some logic to the Santa situation and realized my presents came from somewhere real.

Today I realized the internet actually comes from somewhere. That might sound silly, so think of it in Santa Claus terms. Until I was 9, I never put much thought into the concept of Santa Claus. He appeared when he was supposed to and did was he was supposed to. Then one day, I applied some logic to the Santa situation and realized my presents came from somewhere real.

The same applies to the internet. In my house, the internet comes from a little black box. When it breaks, Shaw brings it back. At work, the internet comes from many little black boxes. When it breaks, I whine to the developers and they bring it back.

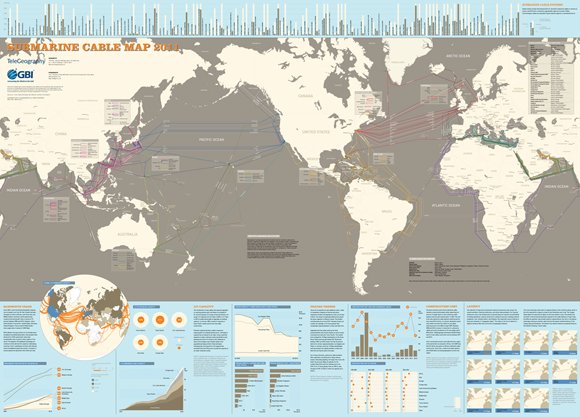

But today, I realized my superficial internet knowledge doesn’t make sense. It must come from somewhere far beyond a mysterious black box with mesmerizing green lights. And then, I stumbled across a map (courtesy of TeleGeography.com) of the world’s internet backbone. Underwater cables!

Turns out, only 1% of the world’s communications are carried out by satellites. The rest rely on this complex tapestry of submarine cables that connects every part of the globe. Well, except Antarctica. They have to rely on silly ol’ satellites and local radio networks.

Feeling clueless? Not for long. Below are all the answers to your burning questions.

How long have undersea cables been around?

Since before the invention of the telephone! The first Trans-Atlantic cable was a telegraph cable laid between 1856 and 1857, but the voltage was too high for the insulation and it failed after only a month. A successful cable was laid along the same route, from Ireland to Newfoundland, almost 10 years later and lasted a decade. The first telephone cable wasn’t laid until 1956.

How many cables are there?

There are currently around 120 cables, plus another 25 planned to be in place by 2013. But these numbers only include the ones currently in use, not discarded cables or ones recommissioned for scientific purposes, like earthquake detection.

Wait a second. Are the old cables still down there?

Yup. I couldn’t find an exact number as to how many abandoned cables littler the ocean floor, but John Kincey, an expert on transatlantic undersea cables, told Wired that most of the defunct cables, copper or otherwise, are still down there. They’re cleared near the beaches so they don’t interfere with fishing, but it’s not unusual to pull up the wrong cable when you’re trying to repair another one.

How do they get to the bottom of the ocean?

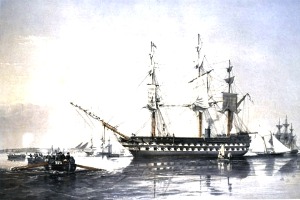

Back when telegraphs were all the rage, cables were laid by converted warships that looked like something out of Pirates of the Caribbean:

Today, fibre-optic cables are laid by specially-built ships that have all sorts of fancy cable-laying thingamajigs, like labs for splicing cable and testing electrical properties, and special propellers that make sure the cable is laid out straight from the stern. Cable layers have to know the lay of the land (the ocean land, that is) so the cable won’t ever be in danger—suspended between two hills, for example, or laid on volcanic activity.

What do fibre-optic submarine cables look like?

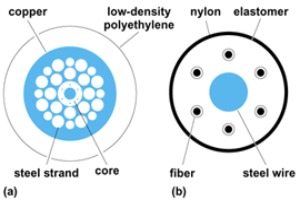

Like this:

This particular cable is 2.5 cm in diameter. Not as exciting as you though, right? There’s a heck of a lot more going on inside the cable:

The deep ocean types, which don’t have a protective steel cable armour, are about 17-20 mm in diameter. Armoured shallow types may be up to 50 mm in diameter. If that sounds backwards to you, it’s not! Shallow water is more energetic than deep water, meaning there’s a lot more going on, like tides, trawlers and hungry sharks. True story. More about that later.

But I want to hear about sharks now!

Okay, fine. If a cable is free-floating for some reason and moving back and forth in the current, sharks will take a bite. In the past two years, sharks have repeatedly dined on the new telephone cable near the Canary Islands. The cost per meal? At least $150,000.

What else damages cables? How do they get fixed?

Tons of things: Anchors, earthquakes, currents, trawlers, pirates. Yes, in 2007, pirates stole an 11-km, 100-ton section of cable and tried to sell it for scrap.

When cables break, shore stations locate breaks by using electrical measurements and a ton of math. The repair ship then heads out, catches the cable using prongs or hooks and splice in a new section.

Are they environmentally friendly?

They’re environmentally neutral. Submarine cables are tiny, non-toxic and stable in salt water. They also make excellent artificial reefs and can be reused for the purposes of environmental monitoring.